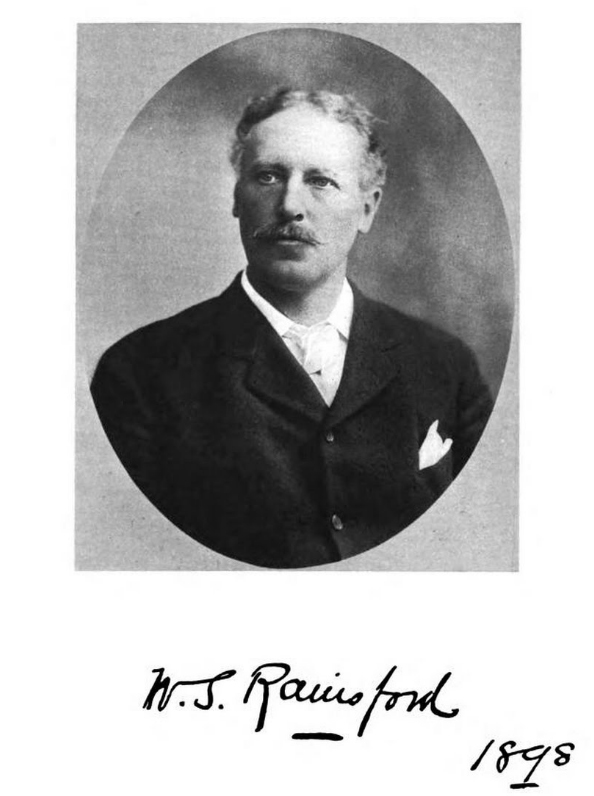

SGCS at 200: The Revolutionary William S. Rainsford

/William S. Rainsford, in The Story of a Varied Life (1922).

This is one of a series of posts celebrating St. George's Choral Society's history during our bicentennial year.

In the late 1800s, St. George’s Church became the first Episcopalian parish to allow female choir members and the first white congregation to hire an African-American soloist. Both were thanks to the vision of one man: reform-minded rector William S. Rainsford.

Rainsford arrived at St. George’s Church in 1883 at age 33. One condition of his accepting the position was ending the practice of renting pews, making the church “absolutely free.”¹ Rainsford turned St. George’s into a parish offering not just worship, but also education and social services.²

His first major reform to St. George’s music program came in the 1880s. As Rainsford wrote in his 1922 autobiography, The Story of a Varied Life:

The next change I strove for was in the church music, and here I first encountered opposition. My plans were revolutionary—nothing less than a new organ, new organist, new choir … I wanted congregational singing.

…

I did dearly want to make the services of the church appeal to all, not part of my people. I wanted a chancel choir, but I wanted it of women as well as of boys and men, and this being my aim, that choir must be a surpliced choir. There lay the difficulty. My vestry was divided. Surpliced choir in old St. George’s! That was too much, even for them.³

Women in religious vestments (surplices) singing in a church choir was revolutionary at the time—it’s not surprising that the decision led several members of the church to leave. Rainsford wrote that St. George’s most famous benefactor and member, J. P. Morgan, “took a good deal of persuading before I got him to my view. But he came to it finally, and then headed the list of subscribers that put up the very considerable amount of money my changes called for.”⁴

In 1902, suffragist and social activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote about Rainsford’s mixed choir in an article for the Baltimore Sun. She quoted church officials opposed to his efforts, including one who described female choir members singing in surplices “an abomination,” and another who stated that if women must sing in a vested chorus, “they should be as inconspicuous as possible.”⁵

Stanton, unsurprisingly, disagreed. She wrote, “All praise to those clergymen and to Dr. Rainsford, who 15 years ago led the way in giving the church a new idea of its duty in regard to the emancipation of women.”⁶

Rainsford also faced opposition when he hired African-American baritone Harry T. Burleigh as a church soloist in 1894. He wrote in his autobiography:

I can only recall, in all those years, one serious commotion in my white-robed company. That was on the memorable occasion when, without warning (for this course I thought the wisest), I broke the news to them that I was going to have for soloist a Negro, Harry Burleigh. Then division, consternation, confusion, and protest reigned for a time. I never knew how the troubled waters settled down. Indeed, I carefully avoided knowing who was for and who against my revolutionary arrangement. Nothing like it had ever been known in the church's musical history. The thing was arranged and I gave no opportunity for its discussion. When the question is one of church policy, I held, and hold, that the decision lies with the rector and with none other.⁷

On this occasion once again, J. P. Morgan stood by Rainsford. He approved immediately of Burleigh’s hiring, and even invited Burleigh into his home to sing every Christmas.⁸

After more than 20 years as rector, Rainsford resigned from St. George’s Church in 1906. He died in 1933 at age 84.⁹

References

1. William Stephen Rainsford, The Story of a Varied Life: An Autobiography (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1922), p. 201. [accessed 25 September 2017].

2. ‘Rainsford, William Stephen’, The Episcopal Church. [accessed 25 September 2017].

3. Rainsford, p. 213.

4. Rainsford, p. 214.

5. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, ‘Women in Church Choirs: Their Right to Wear Ecclesiastical Vestments and March in Processionals’, The Sun (1837-1991); Baltimore, Md. (6 July 1902), p. 12.

6. Stanton.

7. Rainsford, p. 217.

8. Snyder, Jean E. Harry T. Burleigh. (University of Illinois Press, 2016), p. 219.

9. “DR. W.S. RAINSFORD DIES IN 84TH YEAR.” The New York Times. (18 December 1933), p. 19. [accessed 25 September 2017].