Antonin Dvorak, Harry T. Burleigh, and St. George’s Choral Society

/In 1891, St. George’s Choral Society performed Antonín Dvořák’s Stabat Mater for the first time, just 14 years after its completion. We will perform the piece again on April 30, 2017 to celebrate our 200th anniversary and historic connection to the composer. In February 1892, seven months before Dvořák arrived in America, the Choral Society gave the American premiere of his Requiem mass.¹

Jeanette Meyers Thurber in 1892. Image from the Muzeum Antonína Dvořáka.

Dvořák came to America at the invitation of music patron and entrepreneur Jeanette Meyers Thurber. When she opened the National Conservatory of Music of America in 1885, Thurber created a home for the development of American music. Unlike most institutions of the time, Thurber’s National Conservatory recruited talented musicians and composers regardless of sex, race, physical handicap, or financial limitations.²

One of Thurber’s most storied achievements was successfully convincing Antonín Dvořák to leave Prague for New York in September 1892 to become the school’s second director. She offered him a then unheard of annual salary of $15,000 and summers off. Dvořák and his family stayed in New York City for three productive years, leaving in the midst of a national financial panic that made his contracted rate unsustainable.³

At the National Conservatory, Dvořák grew close to gifted African-American student Harry T. Burleigh. Burleigh connected Dvořák to the Black spiritual tradition, and was greatly influential to the writing of his New World Symphony. Burleigh frequently visited and sang spirituals at Dvořák’s home at 327 East 17th Street, a stone’s throw away from both the National Conservatory and St. George's Church.⁴

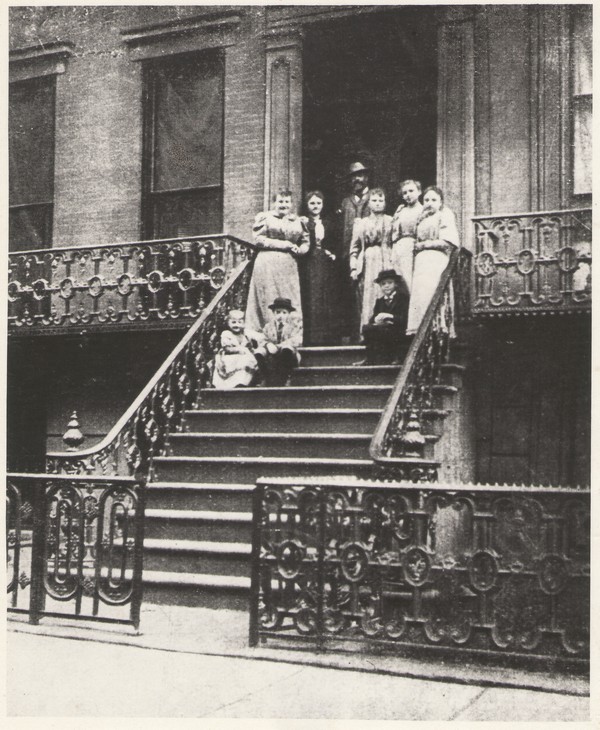

Dvorak and family in front of their New York City home. Image from MUZEUM ANTONÍNA DVOŘÁKA via Harmonie Online.

In 1894, Thurber learned that St. George’s Church needed a new baritone soloist. She arranged with Rector Dr. William S. Rainsford for Burleigh to audition. Burleigh was one of 60 singers to audition behind a screen, and history was made: he became the first African-American soloist of a white congregation. He sang with St. George’s Church and St. George’s Choral Society until retiring in 1946 (the same year Thurber died, just shy of her 96th birthday).⁵

Dvorak statue by Ivan Mestrovic (1883–1962) in Stuvesant Square. Courtesy of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation.

Nearly 100 years after Dvořák arrived in America, his New York home lost its landmark status and was demolished, despite the preservation efforts of groups including St. George’s Choral Society. Though the home was lost, the Choral Society performed works by Dvořák to help fund the installation of a statue of the composer in Stuyvesant Square. This successful effort was led by the Dvořák American Heritage Association, New York Philharmonic, and Stuyvesant Park Neighborhood Association. The statue was dedicated in 1997, a lasting tribute to a composer tied forever to New York City and fondly remembered by St. George’s Church and St. George’s Choral Society.⁶

References

1. ‘Amusements: Church Choral Society’, New York Times, 26 February 1892, p. 5.

2. Emanuel Rubin, ‘Jeannette Meyers Thurber and the National Conservatory of Music’, American Music, 8.3 (1990), 294–325 <https://doi.org/10.2307/3052098>.

3. Michael Cooper, ‘The Deal That Brought Dvorak to New York’, The New York Times, 23 August 2013 <http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/24/arts/music/the-deal-that-brought-dvorak-to-new-york.html> [accessed 7 March 2017].

4. Jean E. Snyder, Harry T. Burleigh (University of Illinois Press, 2016) <http://muse.jhu.edu.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/book/44699/> [accessed 7 March 2017].

5. Dvořák in America, 1892-1895, ed. by John C. Tibbetts (Portland, Or: Amadeus Press, 1993), p. 128; ‘Harry T. Burleigh...’, Southwestern Christian Advocate (New Orleans, 12 July 1894), p. 6;

6. NYC Parks, ‘Stuyvesant Square Monuments - Antonin Dvorak: NYC Parks’ <https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/stuyvesant-square/monuments/1784> [accessed 8 March 2017].